I am a long time fan of HP Lovecraft's Dreamlands and, as is obvious if you are reading this blog, of all things Chinese.

There are many instances in Chinese literature and folk tales of men travelling to a kind of Chinese equivalent of the Dreamlands, which are usually portrayed as a place where the society of men is replaced by that of animals like ants or of mythological beings like dragons, but being in all other aspects very similar to Imperial China. Thus dragonfolk exhibit the same filial piety as the Chinese do, and the society of ants is governed by the same laws as that of the Chinese.

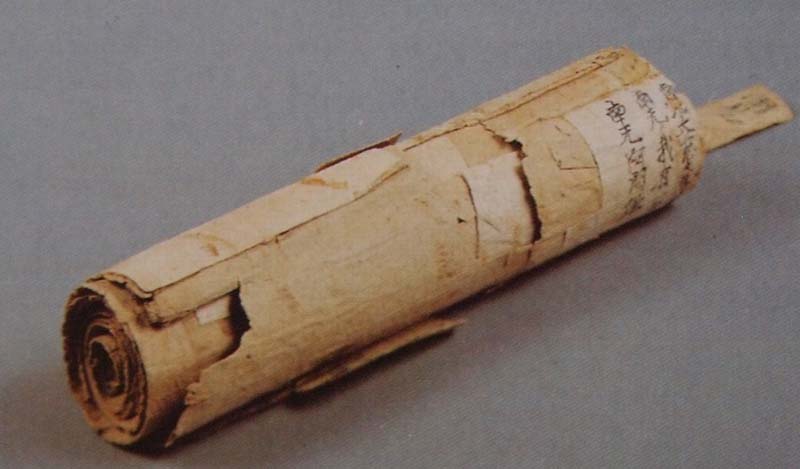

An extremely famous example is the Táng dynasty tale titled the Governor of the Southern Tributary State, in which a disappointed scholar and military man dreams up an entire lifetime of promotion, war, honour, marriage, family and demotion as the governor of the prosperous tributary state of Nánkē, only to suddenly wake up and slowly become aware that it was but a dream, and that a mere half-day has passed in the waking world. The startled man looks around himself, slowly readjusting to reality, and eventually noticing a large ants' nest. The man closely observes the ants' nets and is shocked at the realisation that it is in all aspects identical to the province of which he was the governor. Because of the popularity of this folk tale, the phrase "dream of Nánkē" has become synonymous in Chinese with "inanity of human ambition".

There are other similar tales, and they usually end with some moral teaching. As we can see, whereas Lord Dunsany's or HP Lovecraft's dream-tales are escapist in nature, the Chinese ones are edifying. Which doesn't mean we as players shouldn't enjoy dreamland adventuring in a Chinese setting :)

There are many instances in Chinese literature and folk tales of men travelling to a kind of Chinese equivalent of the Dreamlands, which are usually portrayed as a place where the society of men is replaced by that of animals like ants or of mythological beings like dragons, but being in all other aspects very similar to Imperial China. Thus dragonfolk exhibit the same filial piety as the Chinese do, and the society of ants is governed by the same laws as that of the Chinese.

An extremely famous example is the Táng dynasty tale titled the Governor of the Southern Tributary State, in which a disappointed scholar and military man dreams up an entire lifetime of promotion, war, honour, marriage, family and demotion as the governor of the prosperous tributary state of Nánkē, only to suddenly wake up and slowly become aware that it was but a dream, and that a mere half-day has passed in the waking world. The startled man looks around himself, slowly readjusting to reality, and eventually noticing a large ants' nest. The man closely observes the ants' nets and is shocked at the realisation that it is in all aspects identical to the province of which he was the governor. Because of the popularity of this folk tale, the phrase "dream of Nánkē" has become synonymous in Chinese with "inanity of human ambition".

There are other similar tales, and they usually end with some moral teaching. As we can see, whereas Lord Dunsany's or HP Lovecraft's dream-tales are escapist in nature, the Chinese ones are edifying. Which doesn't mean we as players shouldn't enjoy dreamland adventuring in a Chinese setting :)